How Capitalist Realism Reshaped My Thinking—And My Life

What It Means to See Capitalism for What It Really Is

In high school, I felt incredibly lucky that my school offered a class on investing in the stock market. At the time, I didn’t realize how much that class would shape my entire worldview. Of course, other influences in my life reinforced the idea that success meant winning the rat race. By 16, I had fully embraced capitalism, structuring my entire life around the idea that I wanted to “be so rich that I’d hire someone whose only job was to cut the crust off my PB&J.” I spent years chasing this dream of ultimate wealth, believing that financial success was the key to freedom.

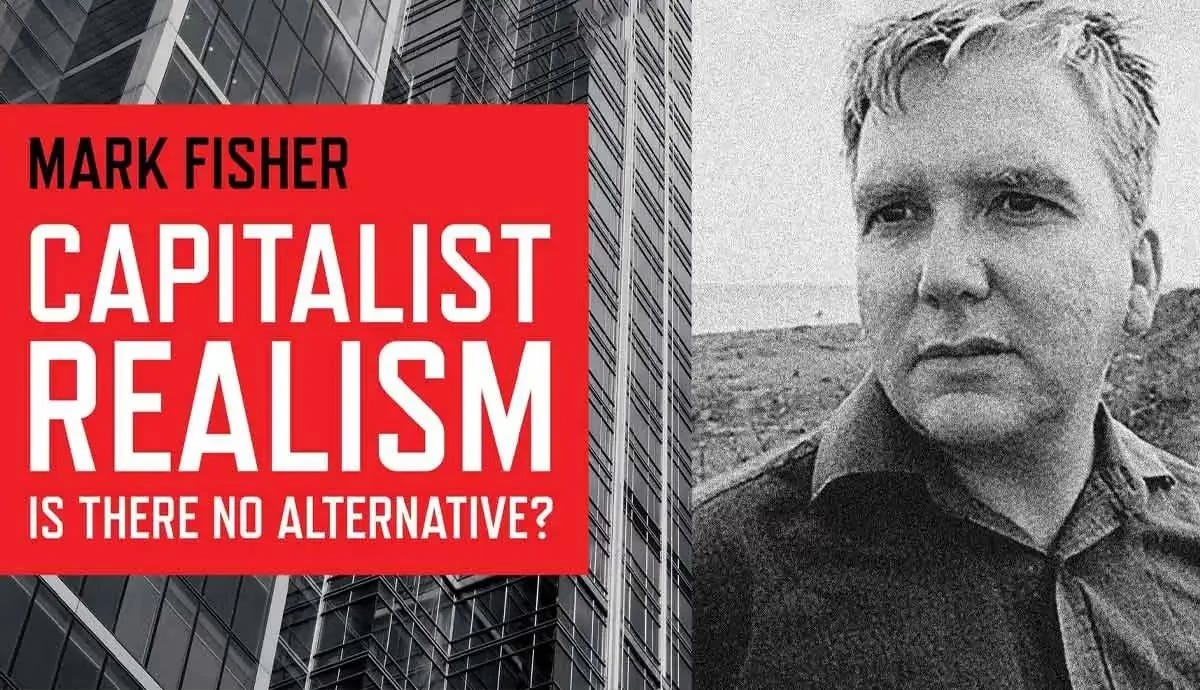

But as I started questioning that dream, Capitalist Realism: Is There Any Alternative? by Mark Fisher accelerated the change that was already underway. Fisher’s book forced me to truly evaluate the world I was operating in, helping me see how deeply Capitalist Realism infects not just the external world, but also my internal reality. I had thought capitalism was simply an economic system, a neutral tool for wealth creation, but Fisher made me realize it was much more than that—it was a pervasive ideology shaping the way we think, work, and even imagine the future.

I won’t go into detail about my blinders-off moment when I first started seeing the world differently, but I want to jump straight into the concept from Capitalist Realism that broke my brain the most: the shift from Discipline Society to Control Society.

Fisher draws from Foucault, but he specifically applies Gilles Deleuze’s expansion of the idea from his essay Postscript on the Societies of Control. Fisher describes the shift as follows:

“Discipline societies were organized around the enclosed spaces of the factory, the school, and the prison. The new control societies, in which all institutions are embedded in a dispersed corporation.”

At first, I felt that Fisher didn’t explain this as well as he could have, so I went back to read Deleuze’s work myself. That’s when I had a realization that’s been messing with my head ever since:

For most of my 20s, I had actually lived inside a Discipline Society—but I didn’t realize it until I was already back in a Control Society.

I grew up in a Control Society like everyone else. It was all I knew. Then my life took a turn—I dropped out of college and joined the Air Force. Suddenly, I was in a world where Discipline Society was still very much alive. The ‘barracks’ in the military represent the old form of discipline: strict rules, clear hierarchies, enclosed environments, and rigid schedules. The means of production was what mattered, and power was enforced physically—you were either in or out.

Leaving the military and returning to civilian life was one of the biggest shocks to my system. In a Discipline Society, power is obvious—there are institutions that enforce rules, and you know who is in charge. But in a Control Society, power is diffused, abstract, and harder to see. I went from an environment where there were clear beginnings and endings (your contract, your training, your enlistment period) to one where everything felt continuous and open-ended.

This is what Deleuze meant when he described Control Societies as a dispersed corporation. There is no one central authority giving orders—power is everywhere and nowhere at the same time. Unlike a factory or a barracks, there are no physical enclosures, but there are financial, digital, and psychological enclosures that control behavior. Fisher argues that:

“Control only works if we are complicit with it.”

This phrase stuck with me, but I didn’t think Fisher fully broke it down. What does it mean to be “complicit” in control? If you’re in a Discipline Society, you resist power by breaking the rules, refusing orders, or escaping the physical space. But in a Control Society, resistance is harder because you are the one enforcing the rules on yourself.

This is where “Indefinite Postponement” comes in. Control Societies don’t rely on enclosure (prisons, schools, barracks)—they rely on debt, bonuses, and never-ending self-improvement cycles to create a new kind of enclosure.

Students stay in school longer because of mounting debt and the pressure to be “competitive.”

Workers never truly clock out—emails, side hustles, and “personal branding” blur the lines between life and labor.

Retirement gets pushed further and further back—the idea of an “end” to work is an illusion.

When I started seeing these patterns, it was hard to unsee them. Unlike Discipline Societies, where power had clear boundaries, Control Societies keep people running in place indefinitely. There’s no clear authority to overthrow because the system perpetuates itself through complicity. You don’t need a warden or a drill instructor telling you what to do—you internalize the expectations and regulate yourself.

At least in the military, there were clear ranks, clear milestones, and a defined endpoint. But in a Control Society, there is no finish line—just an endless loop of productivity, self-improvement, and debt disguised as opportunity. The real trap isn’t that we’re forced to comply; it’s that we convince ourselves we’re doing it by choice.

Fisher doesn’t just critique capitalism—he questions whether we can even imagine something beyond it. Capitalism doesn’t just dominate the world; it dominates our ability to conceive of alternatives. One of the biggest challenges of resistance is that capitalism absorbs its own critiques, turning rebellion into a product.

One of Fisher’s key suggestions for moving forward is worker autonomy—reducing bureaucracy and rejecting the constant surveillance that forces people to self-regulate. This resonates deeply with me. I value autonomy, and I’ve seen firsthand how bureaucracy doesn’t just slow things down but actively conditions people to police themselves.

The biggest problem Fisher highlights isn’t just that capitalism is everywhere—it’s that it makes itself feel inevitable. Even the ways we resist are shaped by its logic. If we try to reform capitalism from within, does that just preserve the same power structures under a new name? Maybe the only way forward isn’t to tweak capitalism, but to shift hard into something else entirely. Neoliberalism has infected capitalism so deeply that it seems impossible to untangle them. If we don’t push for a radical break, will we just keep cycling through slightly different versions of the same system?

Reading Capitalist Realism has fundamentally changed the way I view the world. Through both this book and my lived experiences, I have undergone a complete and radical shift—I now believe that socialism is the way forward, not just in economic practice, but socially. Fisher has made me realize that capitalism doesn’t just shape our economy—it shapes how we relate to one another, keeping us isolated, competitive, and disconnected. A truly better world is one where we move toward collective care, empathy, and solidarity with our neighbors and strangers.

At the same time, Fisher has made me realize that resistance is ten times harder than I once thought. He highlights just how much of a Herculean task it is to change a system where the wealthiest 1% benefit too much to ever let it happen willingly. This realization doesn’t discourage me—it motivates me. If nothing else, this book has reinforced the importance of awareness. That’s why I want to continue writing and having these conversations—because the first step to change is understanding the race we are in.

I’m not frustrated with Fisher for not providing a roadmap. The task of reshaping our future is too big for any one person to dictate a solution. This is something that will require people across the country, across the world, to come together, deliberate, and experiment with what actually works—whether that means reforming or completely breaking away from capitalism. The first step isn’t having all the answers; it’s believing that change is possible.

Resistance isn’t just about having a fully formed alternative—it’s about making space to imagine one. We have to believe we can change the world in order to start the process of doing it.

Ultimately, I thoroughly enjoyed this book, and it has changed my life for the better. It will hold a special place in my heart for that.

Well, along comes AI, making human labor much less needed for most corporations. These corporations shed as many workers as they can, which is great for profits until the corporations run out of customers able to buy because they are unemployed. So the Capitalist system grinds to a halt until an otherwise unimagined economic and social system arises, possibly after the great climate calamity and population die-off. Perhaps, the surviving humans will have learned to cooperate to the extent that they can evolve a new system that is not based on greed.